Stew’s Introduction

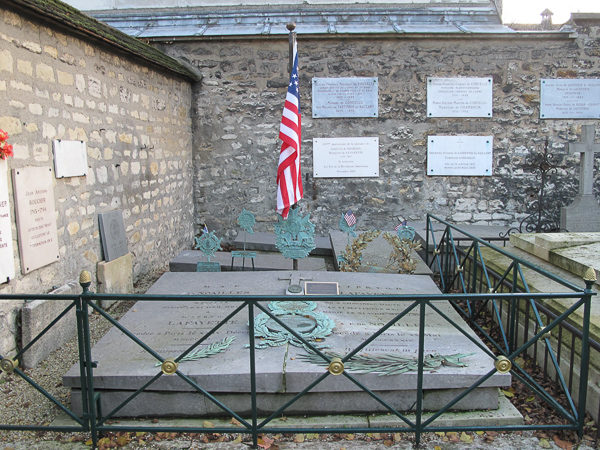

I’m very excited to have Geri Walton as our guest blogger today. Geri is an accomplished history author specializing in an era that corresponds to the English Georgian Era (more on that later). Her blog title concerns a woman who led an extraordinary life and was witness to some of the world’s leading events. It is also about a woman whose passion for her husband likely resulted in her untimely demise. Her subject, the surrounding events, and Picpus Cemetery occupied several pages of my two-volume series on the French Revolution (Where Did They Put the Guillotine? A Walking Tour of Revolutionary Paris). Lafayette lived a long life and frankly, I’m amazed he never lost his head during the Revolution. Neither side (monarchy or revolutionaries) really liked him. Geri mentions Picpus Cemetery in her opening paragraph. It is my favorite Paris cemetery and only one of two privately owned cemeteries located in the city.

Meet Adrienne de Noailles and Her Family

One of the most interesting people buried at France’s Picpus Cemetery is Adrienne de Noailles (1759–1807), wife of the famous American Revolutionary War hero known simply as Lafayette (1757–1834). Adrienne was 14 years old when she married him. She was introduced to Lafayette through her father, a French nobleman named Jean de Noailles, Duke of Ayen.

Adrienne’s mother was Henriette Anne Louise d’Aguesseau. Henriette’s father sent her to a convent to be educated because her mother died shortly after she was born. At the convent, Henriette enjoyed reading and gardening and acquired superb mothering skills that resulted in her devoting her life to the betterment of Adrienne and her other children.

When Adrienne was not under the care of her loving mother, she and her older sister, Anne Jeanne Baptiste Louise (known as Louise), were instructed by a governess named Mademoiselle Marin. They studied geography, grammar, history and learned the “Catéchisme de Montpellier” by rote. Marin was “a little person, dry, thin, blond, pinched, susceptible, devoted to her duties and fulfilling them admirably” and doing so despite Louise and Adrienne’s constant teasing.

Adrienne, Meet Your New Husband

Around the time that Lafayette received his commission, Adrienne’s father was seeking husbands for his daughters. At the time, Louise was 13 and Adrienne 12. When the Duke of Ayen broached the subject with his wife, according to Adrienne, her mother was anguished and thought her girls too young for marriage. However, she decided to “throw herself in to the arms of God and await his will with patient courage.”

Eventually, the Duke and the Duchess reached an agreement. Louise married first in 1773. That same year Adrienne and Lafayette’s marriage contract was signed, and a year later, on 11 April 1774, Adrienne and Lafayette were married.

For the next few years, Adrienne and Lafayette’s social life remained busy, but Adrienne and Lafayette could not have been more at odds over social affairs. Adrienne loved them as much as Lafayette hated them. Part of Lafayette’s dislike was because he was ill-suited for court life. For example, he once found himself dancing a quadrille with Marie-Antoinette, and he was so awkward and clumsy that she and her ladies laughed at him.

The American Revolution

Lafayette became enamored with the American Revolutionary War and wanted to go to America to make a name for himself. He had inherited an extremely large sum of money, which was also one of the reasons that Adrienne’s mother had objected to him as a husband for Adrienne. However, his fortune allowed him to acquire and outfit a ship named the Victorie. He set sail for America on 20 April 1777 and he remained there (with a few occasional trips home) until 22 January 1782, at which time he was received at Versailles and hailed as a hero.

Adrienne had always supported Lafayette’s efforts:

“She bore him [Lafayette] several children, and tended him and them with that expansive maternal solicitude that seems to be the higher part of wifely affection, but, in addition, to these family interests, she aided her husband in all his efforts in the cause of liberty. … Her strength of character indeed was as great as that of Lafayette himself, perhaps greater.”

The French Revolution and the Guillotine

After Lafayette’s return from America, he remained politically active. When the French Revolution broke out, Lafayette was in the thick of things again and eventually found himself imprisoned at Olmütz. During this time, Adrienne’s grandmother, mother, and sister Louise were arrested and guillotined on 22 July 1794. Adrienne was also arrested, but fortunately three influential Americans — Gouverneur Morris, James Monroe, and Elizabeth Monroe — intervened on her behalf, and their intervention resulted in her release on 22 January 1795.

Exile, Imprisonment, and Napoléon

Three months later, in April, to ensure her son’s safety, Adrienne wisely sent 16-year-old Georges Washington to America. She and her daughters then travelled to Vienna, and she requested that she and her daughters, Anastasie and Virginie, be allowed to share in her husband’s imprisonment. Adrienne’s request was granted, and they joined Lafayette at Olmütz in 15 October 1795.

Their imprisonment became worldwide news. It also resulted in a play, The Prisoners of Olmütz, or Conjugal Devotion, being written and performed. The play and news of their imprisonment popularized the family’s plight and resulted in the family’s release on 18 September 1797.

Unfortunately, for Lafayette, when he was released, he was a man without a country. He could not return to France and he was not a citizen of the U.S., so, Adrienne returned to Paris alone. She then proposed to Napoléon that her husband be allowed to return if he would pledge his support and stay out of the public spotlight. Napoléon agreed and Lafayette cooperated, which caused Napoléon to soften his stance, and he restored Lafayette’s French citizenship on 1 March 1800.

Adrienne’s Later Years

Besides being described as “a heroine whose dignity and resolution were as conspicuous as her gentleness,” Adrienne was also declared as being someone who possessed “rare devotion” and was a “flawless partner.” One newspaper printed the following:

“Writing of her after her death the great patriot [Lafayette] praised her not so much for having sped to Olmütz ‘on the wings of love and duty,’ but for ‘having remained in France until she secured as far as lay in her power the materials comforts of my aunt, and the rights of my creditors;’ and for having had the courage to send Georges (their son) to America.”

Adrienne had a hard and difficult life partly because of the losses of loved ones and partly because she suffered chronic health problems after her incarcerations. She dealt with her health problems by using astringents, herbs, plasters, emetics, botanicals, anti-inflammatories, and leeches. Some people believe that her death was directly related to an illness she contracted while at Olmütz. Others suggest that although she may have been suffering from chronic illness, what killed her was lead poisoning. One twenty-first century writer notes:

“The symptoms of her last illness — intense stomach pain, headaches, hallucinations, vomiting, delirium, and convulsions — are all consistent with [lead poisoning].”

A doctor traveling in the area visited Adrienne at her home, known as La Grange, just before Christmas. He diagnosed her with “a defect in the pylorus.” On Christmas Eve, she had recovered enough to spend time with her family, who surrounded her at her bedside. She died that same evening after speaking these last words to her beloved husband Lafayette, “Je suis toute à vous” (“I am all yours”).

Meet Geri Walton

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to get a degree in history and resulted in her website, http://www.geriwalton.com/, which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s. Her first book, Marie Antoinettes’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, discusses the French Revolution and looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe.

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to get a degree in history and resulted in her website, http://www.geriwalton.com/, which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s. Her first book, Marie Antoinettes’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, discusses the French Revolution and looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe.

You can find Geri on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/geri.walton), Twitter (@18thCand19thC), Instagram (@18thand19thc), and Pinterest (https://www.pinterest.com/geriwalton9/).

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2017 Stew Ross

[…] Today I am a lucky enough to be the guest of Stewart Ross at his fabulous blog, “Stew Ross Discovers.” Stew has written several books about France, including “Where Did They Put the Guillotine?” and “Where Did They Burn the Last Grand Master of the Knights Templar?” My guest post is about the Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne. Adrienne was the daughter of Jean de Noailles and Henriette Anne Louise d’Aguesseau, and she married Lafayette when she was 14 years old. Click here to read more. […]

I so enjoyed reading this entry. Lafayette and his wife are heroes to me. I wish more Americans were aware of his devotion to the cause of liberty here.

Hi Debra; Thanks for contacting us about Geri’s guest blog. I agree, it was a very readable piece. I came to know Lafayette and his wife (and her family) while researching my first two books on the French Revolution. Theirs is a remarkable story. I’ve commented to many people how I’m amazed that Lafayette came out of that period of time with his head still attached. No one liked him. The revolutionaries and guard thought he was a noble and close to the monarchy while the king and queen never trusted him. Again, thanks for visiting the blog and I hope you’ll consider subscribing to our bi-weekly blogs. STEW